3 Stories

Architecture, Vanessa, and hands...

A couple of years ago, I was bored taking care of my one-year-old inside our house. I didn't want to go to the playground again, I didn't want to go shopping with her again, and I couldn't stand to stay in the house for another second. I ended up deciding to visit this university that was nearby. I don't really know what compelled me to go.

I remember taking her up close to a fountain with the big lecture halls in the background. She looked at me as if trying to tell me that she wanted to jump in. I said we can't do that. I remember looking up to take in my surroundings. All around me were squares and rectangles of stone, tall lecture halls that feel like they go on forever, and red-tile roofs that remind me of Spanish looking houses. The manicured lawns were pristine and the saplings lining the wide walkways were all 10 feet apart. The only thing that was amiss was my child running wildly away from me, going from walkway to the grass down the sloped hill, not following the path. The college students didn't know what to make of us or how to navigate around this toddling child. I thought to myself that once we were all these young creatures not giving a damn about the walkway and going our own path; then we somehow transform into these college students wearing Airpods, paralyzed in front of a toddler, not knowing how to make sense of things that don't follow a path. Of course, we learn many things that help us along the way to becoming a citizen of this society, some very crucial things. But there is something very essential that we shed off from child to young adult.

I was at first repulsed by the architecture. This was when I was first reading Iain McGilchrist. I thought that if this is how we portray our educational institutions, it is most certainly leaning far towards the left hemisphere. I was disgusted especially since this was a time when I wanted to experience more right hemisphere activities. As I walked through the campus more, however, a different feeling was coming through in me. I was in awe. In awe of human ingenuity. I wondered how these ginormous buildings were constructed and how the landscape complemented the buildings. It was beautiful in its own left-hemisphere way. The way to go about sorting out our complex issues (climate change, metacrisis, etc.) isn't to hate these "negative" parts of the world, but to accept it. I am reminded by what Carl R. Rogers said: "the curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change." We should see it in a different light, perhaps from a different perspective, from a different lens. To own it. To turn towards it, instead of away from it. That it can feel like both tragic and brilliant or evil and good or decaying and generating. Maybe the decay will propel you to generate something new.

Vanessa Andreotti, in her book Hospicing Modernity, begins one of her early chapters with this:

Stories that expire can no longer dance with you. They are lethargic or stuck, they can't move things in generative ways anymore, but we often feel we cannot let them go. Many of these expired stories give us a sense of security, purpose, and direction -- precisely because they seem stable and solid. Thus, we become attached to them and get used to their weight in our lives. If we notice they are dying, we refuse to accept it and we put them on life support because we fear the void left in their place when they are no longer there. We forecast that this void will leave us empty, story-less, and that there will be no vitality in this emptiness because everything will be meaningless, pointless, purposeless, and sad. (Machado, 2021)

While Andreotti is talking about stories that society tells itself, I connected with this paragraph because this was what happened in my own life. There were years where I was putting up with an expired story of my own, the story that I was going to "make it" out in the world with whatever career path I chose, that I was going to do something "big". The toughest part was, of course, letting go. Because if I let go, what was I going to do, how was I going to support myself, who was I going to be. These questions are all legitimate, all brought to me by the manager within. The troubling part, at the time, was that there were seemingly no answers within me. There was no voice that was shouting for me to do x, y, or z. It was deadly quiet and that just worried me even more. You don't know what to do with yourself. And you don't truly know if you're going to figure it out. Andreotti writes:

The next step is to figure out a way to release these stories, and -- for at least a minute -- to sit with the mystery of the void we feared. This is where we might discover that our forecast was wrong. We might find that the void consists of both nothingness and everything-ness and that it can be an unlimited source of serenity, sanity, energy, and inspiration.

Then, a big life event happened to me. I got pregnant! My thoughts turned inward towards the baby and suddenly I had a lot to do to get everything ready for new life. Slowly, I felt that I could no longer waste any more time dealing with this expired story. My big life event was partly what pushed me to shed off the story. I'm not sure what would've happened if it didn't happen. I think it's important not to discount what an affect getting pregnant did to me. It was a catalyst given to me from the world to drive me into shedding off this expired story, something that I'd like to think Iain McGilchrist would call responsive evocation, "the world 'calling forth' something in me that in turn 'calls forth' something in the world" (McGilchrist, 2019).

In one of Ester Perel's early podcast episodes, we are introduced to this young married couple "facing challenges around the roles they play in the relationship dynamic. He has defined himself as a calm, saint-like figure. While she, perhaps in reaction to his 'sainthood', plays the part of hysterical woman prone to explosive outbursts." Instead of going straight to the root of the matter, which seemed to be the wife's violent words during their fights, she turns her attention to the husband who thinks he's innocent in this whole ordeal. He views himself as a noble person, a person with a good heart. So to receive backlash when he has such a good view of himself is jarring. Esther comments:

The way he describes the cycle, the escalation, leaves him out of the equation. It’s as if he’s not an active participant here and she’s doing everything on her own. In a dance where you have one person who attacks and one person who stonewalls, it‘s very important to understand that the person who stonewalls contributes in intensifying the pursuit of the other. And the person who pursues contributes to the other withdrawing. Each person is co-creating the other. That is the essence of the dance — especially in negative escalations.

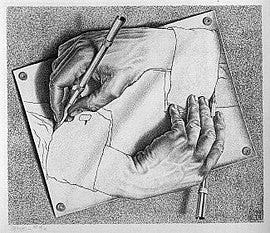

I love the word "co-creating" and "dance" in this. Those words really connect with me. It's like M.C. Escher's hands that draws the hand that draws the hand that draws the hand...

I think what is so crucial about this way of communicating is that Esther does not just tackle her irrational wrath or his victim complex separately. We often think that "we need to work on ourselves" irrespective of what is going on in our environment -- as if we can extricate ourselves from the relationships that are tethered to us. But we don't realize that often, the other person or thing is directly tied to our response. It draws out our response. We are co-creating each other. It is crucial that we don't lose sight of this. Nora Bateson and Vanessa Andreotti gave a talk about this very way of thinking. Nora said this is her opponent -- the monster, the ghost, that we are tackling is "the ghost that doesn't feel the violence of the separations when they're made." Esther is a master at deeply understanding the relational, contextual aspect of her work. When we fail to bring this into our way of thinking, we obscure possibilities that we could have walked down.

Mcgilchrist, I. (2019). The Master and His Emissary : The Divided brain and The Making of the Western World. Yale University Press.

Machado, V. (2021). Hospicing Modernity: parting with harmful ways of living. North Atlantic Books.